Digestion of starch in the rumen requires multiple species of bacteria that associate to form a biofilm on the exposed surface of the grain. It requires complementary species acting in unison as cellulolytic species are needed to degrade endosperm cell walls to enable other species to attack starch granules. Protozoa also engulf starch granules and serve to regulate the rate of starch digestion and moderate pH decline given their slower digestion rate and attachment to particulate matter thus exiting the rumen much slower than bacteria.

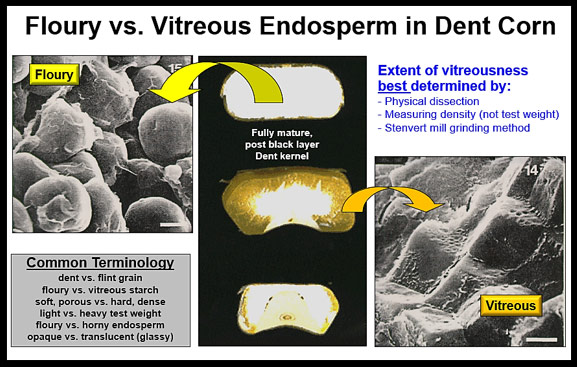

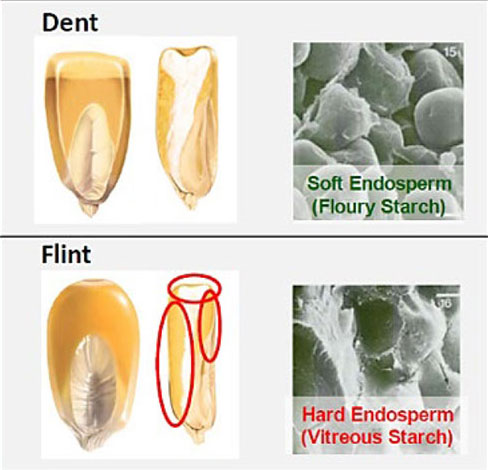

The rate of access to starch granules is governed by endosperm cell walls and the protein (prolamin, zein) matrix. The zein matrix in corn is resistant to proteolytic attack and restricts access of bacterial amylases to the starch granules. Cereals like barley are more rapidly digested because their starch granules are more loosely associated with the protein matrix and that matrix is more readily penetrated by a variety of proteolytic bacteria.

Microbial fermentation of starch produces the volatile fatty acids (VFA) propionate, acetate and butyrate but starch rich diets tend to increase the proportion of propionate. Propionate is absorbed through the rumen wall and transported via the portal vein to the liver where a series of enzymatic reactions (gluconeogenesis) converts it to glucose. Propionate contributes over 50% of the glucose requirement of dairy cows and is critical for the synthesis of lactose which regulates the amount of milk volume the cow produces.

Too little starch digestion in the rumen reduces propionate production and microbial biomass protein (MBP) flow to the intestines. MBP is an important source of high-quality protein for the cow. Too much ruminal starch digestion can lead to subacute acidosis (SARA) causing off-feed, lower production and the production of conjugated linoleic acid (trans-10, cis-12 CLA) causing reduced butterfat yield.

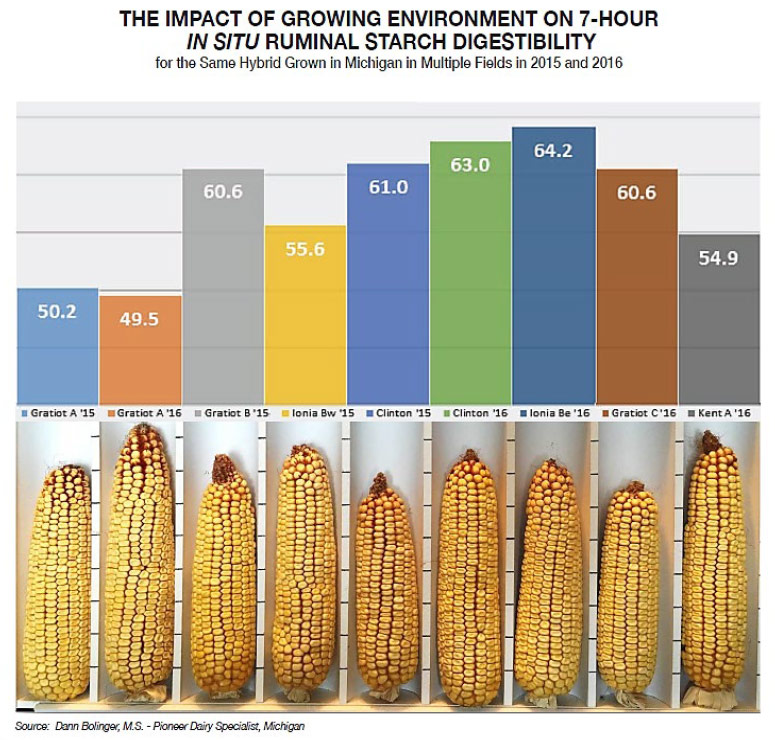

The emergence of a laboratory starch digestibility analysis (7-hour starch digestion) provides an estimate of ruminal starch disappearance but does not account for post-ruminal starch digestion to assess total-tract starch digestion. Fecal starch analysis is a practical approach to evaluate total-track starch digestion. University silage evaluation programs do not include starch digestibility data because it is understood that by the time corn is incorporated into diets, small genetic differences are dwarfed by the influence of growing environment (particularly soil nitrogen fertility), kernel maturity, degree of processing and time in fermented storage.