7/31/2025

Tassel Wrap in Corn

Crop Insights

Written by Mark Jeschke, Ph.D., Pioneer Agronomy Manager; Lucas Borrás, Ph.D., Senior Research Scientist, Corteva Agriscience; and Brent Myers, Ph.D., Senior Data Science Manager, Corteva Agriscience

Key Points

- Tassel wrap – a developmental abnormality of corn in which the uppermost leaves remain wrapped around the emerging tassel instead of unfurling normally – was observed in several states in 2025.

- The widespread occurrence of tassel wrap in 2025 was primarily driven by environmental conditions, with abundant moisture and heat unit accumulation in the growth stages leading up to pollination likely playing a key role.

- Field observations by Corteva scientists suggest that genetic factors also contributed, with corn hybrids characterized by erect leaf architecture in the upper canopy and very aggressive earlier silking more likely to experience tassel wrap.

- In most cases, tassel wrap does not ultimately affect yield; however, reduced kernel set and yield loss can occur if it persists long enough to negatively affect pollination.

- In fields affected by tassel wrap, it is advisable to wait until mid-grain fill stages to evaluate effects on kernel set and its potential yield impact.

Tassel Wrap in 2025

In July of 2025, a phenomenon commonly referred to as “tassel wrap” was observed across several states in which the uppermost leaves on corn plants remained wrapped around the emerging tassel instead of unfurling normally. The tassels wrapped in leaves were often partially or completely obstructed in their ability to shed pollen in a timely manner. In most cases there was little or no impact on kernel set. In some cases, this obstruction persisted long enough to negatively affect pollination and result in reduced kernel set.

Tassel wrap was observed in at least 15 different Midwestern and Southern states in 2025 (Squire and Held, 2025; Corteva data). Numerous hybrids with a range of different trait technologies from multiple different seed brands were affected. Within specific geographies it was not uncommon for tassel wrap to be more prevalent within certain hybrids (Licht, 2025; Quinn, 2025) and fields planted within specific windows (Karhoff et al., 2025; Licht, 2025; Quinn, 2025; Roozeboom et al., 2025). Iowa State associate professor Dr. Mark Licht reported that affected fields had tassel wrap on anywhere from 20% to 80% of plants, with less than 50% of plants affected in most cases (Licht, 2025).

Figure 1. Tassel wrap in a Missouri corn field; July 2, 2025.

Potential Contributing Factors

Agronomists believe this issue was primarily associated with a later than normal manifestation of rapid growth syndrome – a phenomenon that normally appears earlier in the vegetative stages in which an abrupt acceleration in plant growth causes the plant leaves to become tightly wrapped as new leaves emerge faster than existing leaves are able to unfurl (Karhoff et al., 2025; Licht, 2025; Quinn, 2025). When rapid growth syndrome occurs during vegetative growth, it typically resolves on its own and has little or no impact on yield.

Rapid growth syndrome is relatively common in corn and is brought on when environmental conditions suddenly shift from unfavorable to very favorable for corn growth (Jeschke, 2020). When rapid growth syndrome occurs earlier in the growing season, it is most commonly associated with a shift from cooler to warmer temperatures, but it can also involve a shift from overcast to sunny conditions, an increase in soil water availability, or any combination of these factors that cause the plants to sharply transition from slow to rapid growth. This sudden acceleration in growth can cause the leaves in the whorl to become twisted or tightly wrapped, as the inner leaves grow faster than the outer leaves can unfurl. Rapid growth syndrome most commonly occurs at the V5-V6 growth stage but can be observed as late as V12. Occurrences of rapid growth syndrome late enough in the season to impede tassel emergence are less common.

| A sudden acceleration in growth can cause the leaves in the whorl to become twisted or tightly wrapped, as the inner leaves grow faster than the outer leaves can unfurl. |

In addition to a rapid acceleration in growth, other environmentally driven factors may contribute to the occurrence of tassel wrap as well. Environmental conditions during late vegetative growth can cause a shortening of the upper internodes. This can lead to a compression in leaf structure and less room for tassel extension, particularly in cases where corn is shorter overall. Environmental conditions that cause plants to produce smaller tassels with fewer branches may contribute as well, as there is less tassel mass to push the flag leaf open. Fields experiencing tassel wrap in 2025 were noted in some cases as having smaller tassels with fewer branches (Licht, 2025; Quinn, 2025).

Genetic and Environmental Factors in 2025

Field observations by Corteva scientists suggest that occurrences of tassel wrap in 2025 likely involved an interaction of multiple genetic and environmental factors. Hybrids with the most frequent occurrence of tassel wrap tended to have some combination of three characteristics: erect leaf architecture in the upper canopy, minimally branched tassels, and negative anthesis-silking interval. All three of these characteristics have been important in driving yield gain in corn and have been directly or indirectly selected for by corn breeding programs.

| Occurrences of tassel wrap in 2025 likely involved an interaction of multiple genetic and environmental factors. |

The shift toward more upright leaves in corn hybrids that began early in the 1960s has been important for supporting greater plant densities and maximizing radiation use efficiency by enabling light penetration deeper into the canopy (Duvick et al., 2004). Smaller tassels with fewer branches have provided a more optimal allocation of biomass in the plant, favoring photosynthesizing tissues and harvestable yield. And shortening the anthesis-silking interval (the amount of time between pollen shed and silk emergence) has been critically important in improving drought tolerance in corn. All these changes have occurred across US commercial germplasm through selection for higher yields and have not been unique to Corteva/Pioneer.

Figure 2. Comparison of tassels from three hybrids grown side by side. The middle tassel displays tassel wrap, with pollen being released within the upper leaves and only the tip of the tassel exposed. The tassels on either side show normal development and pollen shed.

Of these three characteristics, erect leaf architecture in the upper canopy and very aggressive earlier silking appear to be closely associated with occurrences of tassel wrap problems affecting pollination during 2025.

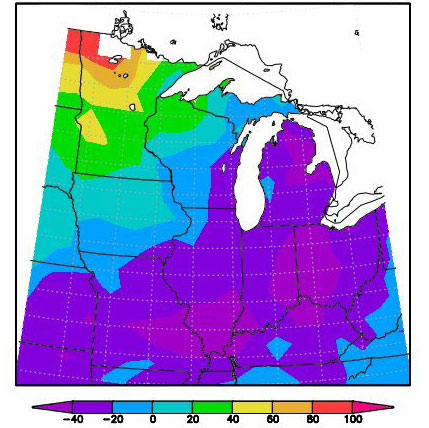

While hybrid characteristics no doubt contributed to tassel wrap, its uniquely widespread occurrence in 2025 clearly demonstrates that abnormal environmental conditions were the dominant driving factor. Above-average total rainfall appears to be the environmental anomaly in 2025 that correlates most to tassel wrap occurrence (Figure 3), specifically more rainfall and lower vapor pressure deficit from V7 to V14 (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Precipitation anomaly for the 120-day period from March 26 to July 23, 2025 (High Plains Regional Climate Center). Areas with the greatest prevalence of tassel wrap in the southern Corn Belt and Midsouth tended to have greater than normal precipitation, although cases were also being reported in northern regions with precipitation closer to normal.

Figure 4. Weather conditions in 2025 compared to the previous 30 years for a set of locations with reported tassel wrap incidents. The data illustrate rainfall, relative humidity, mean temperature, maximum and minimum temperatures, and vapor pressure deficit across key growth stages—planting to tasseling, planting to emergence, emergence to V7, V7 to V14, and V14 to tasseling—for 64 reported tassel wrap cases across the U.S.

(Note: At the time of publication, locations with documented occurrences of tassel wrap were concentrated in the South and Mid-South, as these were the earliest reported cases. Data collection and analysis from Midwestern locations is ongoing.) See the following growth stage charts for more details.

Greater water availability is known to induce more rapid plant growth and earlier appearance of silks relative to pollen shed. Much of the area that experienced tassel wrap also had below average GDU accumulation earlier in the season (Figure 5), so the shift from slow growth to rapid growth conditions may have been a factor.

Figure 5. Growing degree unit accumulation deviation from normal for the period of May 1 to 27, 2025 (Midwestern Regional Climate Center).

Impact on Pollination

Successful pollination depends on the synchronization of pollen shed with the presence of receptive silks. Silks on a corn ear typically emerge over a period of 4 to 8 days. This process is sequential, with silks from the basal portion of the ear emerging first, followed by silks from the middle and tip of the ear. Silks grow about 1 to 1.5 inches a day and will continue to elongate until fertilized. Silks are receptive to pollen for up to 10 days after they emerge from the husk, but their receptivity is highest during the first 4 to 5 days. After about 5 days, silk receptivity begins to decline, and after 10 days, it decreases rapidly due to natural senescence of the silk tissue.

When normal tassel emergence and pollen shed is impeded by leaves remaining wrapped around the tassel, the result can be a delay in pollen shed relative to silk emergence and a reduction in pollen load, both of which can reduce kernel set and – ultimately – yield. This was the case in at least some of the fields impacted by tassel wrap in 2025.

| Silks are receptive to pollen for up to 10 days after they emerge from the husk, with greatest receptivity during the first 4 to 5 days. |

Environmental Factors and Development Issues

Although the 2025 growing season saw the most widespread occurrence of tassel wrap in recent memory, similar situations have occurred in recent years in which an acute stress event or an unusual confluence of environmental conditions during the critical period around silking in corn resulted in occurrences of abnormal crop development appearing over a wide area. Recent examples include 2021, when corn plants producing multiple ears on the same shank were observed across multiple states (Jeschke, 2021) and 2016, when abnormalities in ear development occurred across much of the Western and Central Corn Belt (Jeschke, 2016a, 2016b, 2016c).

In 2021, the development of multiple ears per shank was believed to be associated with a hormonal imbalance triggered by some sort of early season stress that disrupted the apical dominance of the primary ear, followed by favorable growing conditions that allowed secondary ears to develop. Abnormal ear development in 2016 seemed to be associated with a confluence of multiple stress factors, including a rapid transition from cold to hot temperatures, an extended period of low solar radiation, and high winds that damaged plants as they were nearing pollination.

The occurrence of abnormal development issues in corn is partly attributable to the basic biology of the corn plant itself, and the ability of environmental stresses that affect the plant during critical developmental stages to have a lasting effect on plant development. It is not unusual for instances of abnormal development to show up more in some hybrids than in others. In some cases, this may have more to do with crop phenology – the exact stage of development the crop was in when exposed to the environmental conditions that triggered abnormal development – which is a function of hybrid maturity, planting date, and GDU accumulation.

In cases like the one shown in Figure 2, the wrapped tassels begin shedding pollen while still wrapped in the upper leaves. Pollen loses viability as soon as it comes into contact with water.

The pollen shed inside the wrapped leaves is lost and not able to contribute to pollination once the tassel was able to emerge. The tassels will ultimately expand from the leaves and will shed pollen, but significantly later.

Pollen shed across a field of corn typically lasts 10 to 14 days, with around a 4-day period when pollen shed is at its peak. Pollen shed from an individual plant occurs over a shorter period – typically not more than 7 days. Plant-to-plant variability in the timing of peak pollen shed, along with the sheer volume of pollen produced (estimates range from 2 million to 25 million grains per plant), typically provides a margin of safety for achieving complete pollination. Even if unfavorable conditions disrupt pollination for a few days, there is still usually enough time and pollen available to complete pollination without issue.

When pollen shed is impeded for more than a few days, it is possible that incomplete pollination can result. This can be due to insufficient pollen availability during the window of silk receptivity. Since silks continue to elongate until they are fertilized, early emerging silks that remain unfertilized will continue to grow. The resulting mass of silk growth can sometimes obstruct fertilization of newly emerged silks from ovules further up the ear.

Earlier silking respective to pollen shed has been a direct focus of corn breeders for a long time, especially because of its positive effect on drought tolerance. Old hybrids, with lower drought tolerance, tended to extrude silks later than pollen shed when under drought stress, limiting their ability to yield due to limited exposure of silks to pollen availability. Modern high-yielding hybrids have been bred to extrude silks earlier than pollen shed, even under severe drought conditions. The shift in earlier silking has been a key trait responsible for the greater drought tolerance of modern germplasm.

Previous Experiences with Tassel Wrap

The widespread nature of tassel wrap in 2025 meant that many corn growers and agronomists were likely seeing it for the first time, but more limited occurrences were observed by Corteva scientists in previous years, affecting different geographies each year. Prior experience with tassel wrap has shown that, while some hybrid genetics may be more prone to it, all genetics can be affected by it with the right environmental factors. Some older hybrids that experienced tassel wrap in 2025 had never shown it before.

| Some older hybrids that experienced tassel wrap in 2025 had never shown it before. |

In previous years, the vast majority of fields experiencing tassel wrap ultimately saw no impact on corn yield. In cases where the duration of tassel obstruction was sufficient to affect pollination, the most common outcomes were missing kernels concentrated near the base of the ear or on one side of the ear and unevenness of early kernel growth resulting from the fertilization of individual ovules occurring over a longer period of time.

The effect of uneven pollination timing can look worse than it actually is if evaluated too early after fertilization. Ovules that are fertilized a few days later than those adjacent to them will be smaller and lighter in color through the early stages of kernel growth but will even out somewhat as grain fill proceeds (Figure 6). The effect of missing kernels can also not be as bad as it may initially appear.

Figure 6. Ears from a field where tassel wrap resulted in incomplete pollination sampled on July 11 (left) and July 25 (right). Ears sampled on July 11 show missing kernels and inconsistent kernel size and color due to variation in fertilization timing. Ears sampled on July 25 show more consistent kernel color and compensatory growth where kernels adjacent to gaps have expanded into the empty space.

Figure 7. Tassel wrap in a Missouri corn field; July 7, 2025.

| Missing kernels generally have a negative effect on yield but the plant does have some capacity to compensate for missing kernels through greater kernel weight. |

Although missing kernels generally have a negative effect on yield, the plant does have some capacity to compensate for missing kernels through greater kernel weight. Kernels adjacent to gaps will expand into the empty spaces, and kernel weight overall can be greater as the plant allocates the same amount of photosynthate over a smaller number of kernels. Ears with poor pollination at the base often have lower tip kernel abortion. The percentage yield loss will be lower than the percentage of missing kernels (Table 1). In fields affected by tassel wrap, it is advisable to wait until midgrain fill stages to evaluate effects on kernel set and its potential yield impact.

Table 1. Estimated reduction in plant yield associated with incomplete pollination (Borrás et al., 2004; Westgate et al., 2003).

| Kernel Loss (%) | Yield Loss (%) |

|---|---|

| 10 | 2.5 - 4.6 |

| 20 | 7.2 - 11.8 |

| 30 | 18.8 - 20.3 |

| 40 | 30.1 - 30.4 |

| 50 | 41.2 - 42.0 |

| 90 | 70 |

| 72 | 62 |

Conclusions

Each growing season brings a unique set of conditions and challenges and 2025 has been no exception. Abnormal environmental conditions, especially abundant water availability leading up to pollination, were likely the main cause of the higher-than-normal occurrence of tassel wrap in 2025. Earlier silking relative to pollen shed driven by extraordinarily good growing conditions might have exacerbated the problem. The wide geographic range of reported occurrences, as well as the fact that it showed up across numerous different hybrids, trait technologies, and seed brands, clearly points to environmental conditions as the primary driver.

Fields experiencing tassel wrap in previous years usually saw no effect on yield; however, reductions in kernel set associated with tassel wrap were observed in some cases in 2025. Fields that experienced tassel wrap should be evaluated around mid-grain filling and not during or shortly after flowering, so the end effect on kernel set is fully visible. Kernel weight compensation will occur on ears with missing kernels, which means that yield loss will not be directly proportional to the number of missing kernels.

At the time of publication, Corteva scientists and Pioneer agronomists were continuing to collect data on locations where tassel wrap occurred to better understand contributing factors and effects on kernel set and yield.

References

- Borrás, L., G.A. Slafer, and M.E. Otegui. 2004. Seed dry weight response to source–sink manipulations in wheat, maize and soybean: a quantitative reappraisal. Field Crops Res. 86:131-146.

- Duvick, D.N., J.S.C. Smith, and M. Cooper. 2004. Long-term selection in a commercial hybrid maize breeding program. Plant Breeding Reviews 24:109-151.

- Jeschke, M. 2016a. Abnormal Corn Ear Development in 2016 – Illinois and Indiana. Pioneer Field Facts, Vol. 16 No. 18. Corteva Agriscience

- Jeschke, M. 2016b. Abnormal Corn Ear Development in 2016 – Iowa. Pioneer Field Facts, Vol. 16 No. 18. Corteva Agriscience

- Jeschke, M. 2016c. Abnormal Corn Ear Development in 2016 – Illinois and Indiana. Pioneer Field Facts, Vol. 16 No. 18. Corteva Agriscience

- Jeschke, M. 2020. Rapid Growth Syndrome in Corn. Pioneer Crop Focus, Vol. 12 No. 19. Corteva Agriscience.

- Jeschke, M. 2021. Why Do Corn Plants Develop Multiple Ears on the Same Shank? Pioneer Crop Insights, Vol. 31 No. 3. Corteva Agriscience.

- Karhoff, S. A. Wilson, O. Ortez, C. Schroeder, G. LaBarge. 2025. Tight Tassel Wrap in Corn. C.O.R.N. newsletter. Agronomic Crops Network. Ohio St. Univ. Ext.

- Licht, M. 2025. Are you seeing wrapped tassels shedding pollen? We are too! ICM News, July 18, 2025. Iowa State University.

- Quinn, D. 2025. Wrapped Tassels In Corn: Now What? Pest and Crop Newsletter. Purdue University Extension.

- Roozeboom, K., T. Sullivan, and L. Simon. 2025. Corn production: Pollination issues and tightly wrapped tassels. Agronomy eUpdates Issue 1062, July 17, 2025. Kansas State University.

- Squire, M., and A. Held. 2025. Tight Tassel Wrap Is Showing Up in the Corn Belt — Here’s What Farmers Should Know. Successful Farming.

- Westgate, M.E., J. Lizaso, and W. Batchelor. 2003. Quantitative relationships between pollen shed density and grain yield in maize. Crop Sci. 43:934–942.

The foregoing is provided for informational use only. Contact your Pioneer sales professional for information and suggestions specific to your operation. Product performance is variable and subject to any number of environmental, disease, and pest pressures. Individual results may vary. Pioneer® brand products are provided subject to the terms and conditions of purchase which are part of the labeling and purchase documents.