6/20/2025

Foliar Fungicides For Use in Corn

Crop Insights

Written by Mark Jeschke, Ph.D., Pioneer Agronomy Manager

Key Points

- As foliar fungicide use in corn has become more common, the number of products in the marketplace with multiple active ingredients has increased.

- Mode of action is the primary criterion by which fungicides are categorized and target site is the basis for FRAC groups, which are group numbers assigned by the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee that are shown on fungicide product labels.

- Three different groups of fungicides are commonly used in corn: demethylation inhibitors (Group 3), succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors (Group 7), and quinone outside inhibitors (Group 11).

- Fungicides are sometimes referred to as having “preventative” or “curative” activity but both types need to be applied early in the infection process to be effective.

- Fungicides can differ in their mobility both in and on plant tissues.

- Using fungicides with multiple modes of action can help slow the development of resistance in pathogens and provide more effective disease control.

Corn Fungicides

Over the past couple decades, foliar fungicides have gone from a mostly new and untested practice to a trusted component of many growers’ management systems. This has occurred as research results and grower experience have demonstrated that fungicides can be very effective tools for managing foliar diseases and protecting yield in corn.

As foliar fungicide use in corn has become more common, the number of products in the marketplace has increased. Older fungicides typically only had one active ingredient, but many newer ones have two, or even three, active ingredients with different modes of action. With the increasing complexity of fungicide options available to corn growers, it is important to understand different fungicide modes of action, how they work, and good stewardship practices.

Fungicide Mode of Action

Fungicides inhibit fungal growth by disrupting critical processes in fungal cells. Fungicide mode of action (MOA) refers to the cellular process inhibited by a fungicide. Fungicide target site (or site of action) refers to the specific enzyme involved in a cellular process to which a fungicide binds. It is possible for two fungicides to have the same mode of action but different target sites, meaning that they disrupt the same cellular process but target different enzymes involved in the process to do so.

Target site is the basis for FRAC codes, which are group numbers assigned by the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee that are shown on fungicide product labels (Figure 1). A pathogen that develops resistance to a specific fungicide will generally also be resistant to other fungicides that share the same target site, a phenomenon known as cross resistance. Consequently, from a resistance management standpoint, target site is the most important distinguishing factor for categorizing fungicides.

Fungicides within a target site grouping are also sometimes further subdivided into chemical groups, which are based on structural characteristics of the fungicide molecules.

Figure 1. Example of a fungicide product label showing the names and FRAC groups of the active ingredients.

FRAC currently recognizes 12 different known fungicide modes of action. Of these, two are currently utilized in foliar fungicide products used in corn: inhibition of cellular respiration or inhibition of sterol biosynthesis in cell membranes. This includes three different FRAC groups (target sites), two of which share the same mode of action:

- Group 3: Demethylation Inhibitors (DMI) - sterol biosynthesis

- Group 7: Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors (SDHI) - cellular respiration

- Group 11: Quinone Outside Inhibitors (QoI) - cellular respiration

In practice, the term “mode of action” is often used in place of target site or FRAC group, despite not being technically accurate. For example, SDHI and QoI fungicides have the same mode of action, as they both work by inhibiting cellular respiration. In common usage though, they are generally referred to as different “modes of action” because they have different target sites, do not exhibit cross resistance, and are in different FRAC groups.

Preventative vs. Curative Fungicides

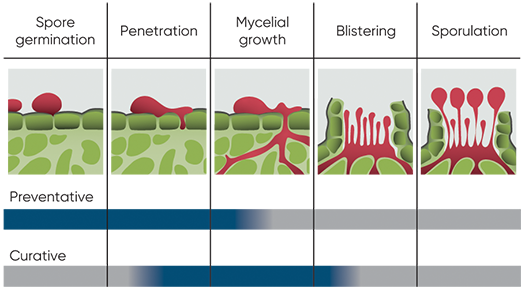

Fungicides are sometimes referred to as having “preventative” or “curative” activity (Mueller and Robertson, 2008). This distinction is based on the stage of fungal infection that is disrupted by a particular fungicide mode of action. These terms can be somewhat misleading however, as no fungicides are truly curative – once plant tissue has been damaged by fungal infection, it cannot be recovered. Both types of fungicides need to be present early in the infection process to be effective.

QoI and SDHI fungicides are considered preventative fungicides. The mode of action for both types of fungicides is inhibition of cellular respiration, which means that they kill the fungus by stopping energy production in the mitochondria of the fungal cells. QoI fungicides usually accumulate in the waxy cuticle on the leaf surface, and do not prevent growth of fungal mycelium inside leaf tissue. If fungal spores are exposed to QoI or SDHI fungicides before they germinate, the germination process is stopped, and infection is prevented. QoI and SDHI fungicides both need to be applied prior to infection or in the very early stages of infection to be effective (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Stages of fungal infection and efficacy windows of “preventative” and “curative” fungicides..

Most DMI active ingredients are considered curative fungicides. DMI fungicides are absorbed into the leaf tissue and disrupt fungal development early in the infection process. The mode of action for these fungicides is inhibition of sterol production, which is a type of lipid molecule required to form cell membranes. A fungal spore exposed to a DMI fungicide can still germinate but once the supply of sterols in the spores is depleted, fungal growth stops. Despite being characterized as “curative,” DMI fungicides still need to be applied prior to infection or in the very early stages of infection to be effective.

It is important to remember that infection can begin well before visual symptoms of foliar diseases become apparent. The period from the start of infection until visual symptoms develop is known as the latent period. The length of this period differs among foliar diseases – from as little as 3 days for southern rust to 3 weeks or more for gray leaf spot (Table 1). The major fungal foliar diseases of corn are all polycyclic, which means that many disease cycles can occur in a single season and new infections will continue to occur as long as conditions are favorable and susceptible plant tissue is available.

Table 1. Approximate latent periods of common corn diseases.

| Corn Disease | Latent Period |

|---|---|

| Southern rust (Puccinia polysora) | 3-4 days |

| Common rust (Puccinia sorghi) | 6-7 days |

| Northern leaf blight (Exserohilum turcicum) | 7-14 days |

| Tar spot (Phyllachora maydis) | 14-20 days |

| Gray leaf spot (Cercospora zeae-maydis) | 14-28 days |

Fungicide Mobility

Fungicides can differ in their mobility both in and on plant tissues. Fungicides are broadly classified as either contact or penetrant (Oliver and Beckerman, 2022):

Contact fungicides, also known as protectants, are adsorbed to plant surfaces where they form a thin protective layer that prevents spore germination. Contact fungicides must be applied before spores land on the leaves to be effective, as they have no protective effect once infection has already begun. Many older fungicides are protectants.

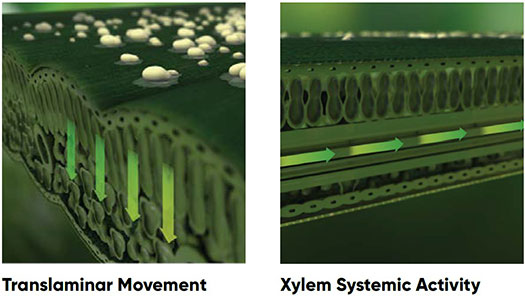

Penetrant fungicides penetrate the waxy cuticle on the leaves and are absorbed into plant tissues, where they can have varying degrees of mobility within the plant (Figure 3):

Figure 3. Different types of fungicide mobility.

- Translaminar – The fungicide is absorbed into the leaf tissue and can penetrate through the leaf to the opposite surface but does not move throughout the plant.

- Locally systemic – The fungicide undergoes very limited translocation in plant tissues, not moving far from the site of penetration.

- Xylem mobile – The fungicide is translocated via the xylem tissue, which allows it to move upward in the plant from the site of penetration but not downward.

Very few fungicides (and none currently used in corn) are fully systemic within plants, which would require translocation via both the xylem and phloem tissues allowing both upward and downward movement in the plant.

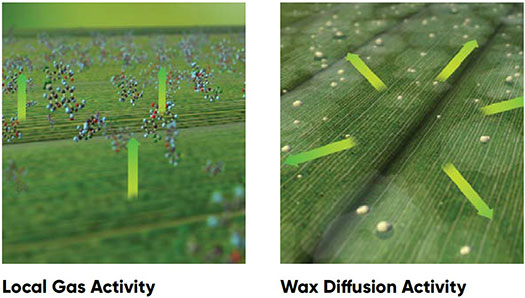

Fungicides can also move outside the plant. Surface redistribution occurs when rewetting of leaf tissue after application allows the fungicide to spread locally on the leaf’s surface from the point of application. Some fungicides also have vapor phase mobility, which means that they can redistribute within the crop canopy via vapor movement following application, allowing them to move from leaf to leaf and have activity in plant tissues that were not directly exposed to the initial application (Figure 3):

All three classes of fungicides currently used in corn are classified as penetrants, as they all are absorbed into plant tissues and have some degree of mobility within plants (Oliver and Beckerman, 2022). SDHI fungicides (Group 7) are the least mobile, only having locally systemic distribution within plant tissues. QoI fungicides (Group 11) vary in their mobility. Most have only locally systemic and translaminar mobility in plants; however, azoxystrobin and picoxystrobin are both translaminar and xylem mobile, and picoxystrobin further exhibits vapor movement within the canopy. DMI fungicides (Group 3) are the most mobile, with all members of this group able to translocate upward in plants via the xylem tissue.

Group 3: Demethylation Inhibitors (DMI)

- Mode of Action: Sterol biosynthesis in membranes

- Target Site: C14-demethylase in sterol biosynthesis

- Mobility: Xylem-mobile

- Resistance Risk: Medium

Group 3 fungicides are commonly referred to as the triazoles, as most of the active ingredients used in corn come from this chemical group (Table 2). These fungicides were first introduced in the mid-1970s and are effective against many fungal diseases, especially rusts and leaf spots. Corn fungicide products containing only a DMI active ingredient are available, although many current fungicides combine a DMI with a Group 11 fungicide (strobilurin), as well as three-way products that also include a Group 7 fungicide.

Table 2. Group 3 DMI fungicide active ingredients used in fungicide products labelled for control of foliar diseases in corn.

| Common Name | Chemical Group |

|---|---|

| cyproconazole | triazoles |

| flutriafol | triazoles |

| mefentrifluconazole | triazoles |

| metconazole | triazoles |

| propiconazolen | triazoles |

| tebuconazole | triazoles |

| tetraconazolen | triazoles |

| prothioconazole | triazolinthiones |

DMI fungicides work by inhibiting C14-demethylase, an enzyme that plays a role in sterol production. Although all DMI fungicides target this enzyme, different active ingredients may act in slightly different parts of the biochemical pathway, resulting in differing spectra of activity for these fungicides (Mueller et al., 2013).

DMI fungicides are locally systemic and xylem-mobile, which means they can spread in the leaf tissue from the site of application and move upward in the plant via the xylem tissue. These fungicides typically have around 14 days of residual activity after application.

DMI fungicides are considered medium risk for resistance development. Resistance has been documented in multiple fungal species, with multiple known mechanisms of resistance (FRAC, 2024). Reduced sensitivity to certain DMI fungicides has been reported in several U.S. states for Fusarium graminearum (fusarium head blight) in wheat. Recent research suggests that there may be isolates of Exserohilum turcicum – the causal pathogen of northern corn leaf blight – that are resistant to the DMI fungicide flutriafol (Anderson et al., 2024).

Group 7 Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors (SDHI)

- Mode of Action: Cellular respiration

- Target Site: Complex II: succinate-dehydrogenase

- Mobility: Locally systemic

- Resistance Risk: Medium-high

SDHI fungicides have been on the market since the late 1960s. The first generation of these fungicides had relatively limited disease and application spectra. SDHI fungicides with increased spectrum and potency were commercialized beginning in the early 2000s and new ones continue to be launched today. Corn fungicide products that include a SDHI typically also include a Group 3 or Group 11 fungicide, or both.

SDHI fungicides inhibit complex II of the fungal mitochondrial respiration pathway by binding and blocking SDH-mediated electron transfer from succinate to ubiquinone. SDHI fungicides are locally systemic, capable of moving a short distance from the site of application. SDHIs have longer residual activity than other groups.

Resistance to SDHI fungicides has been documented in several fungal pathogens. Field isolates with target site mutations conferring reduced sensitivity have been found in Pyrenophora teres (net blotch) in barley, Zymoseptoria tritici (septoria leaf blotch) in wheat and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (sclerotinia stem rot) in canola (FRAC, 2015).

Table 3. Group 7 SDHI fungicide active ingredients used in fungicide products labelled for control of foliar diseases in corn.

| Common Name | Chemical Group |

|---|---|

| fluopyram | pyridinyl-ethyl-benzamides |

| benzovindiflupyr | pyrazole-4-carboxamides |

| bixafen | pyrazole-4-carboxamides |

| fluindapyr | pyrazole-4-carboxamides |

| fluxapyroxad | pyrazole-4-carboxamides |

| pydiflumetofen | N-methoxy-(phenyl-ethyl)-pyrazole-carboxamides |

Group 11 Quinone Outside Inhibitors (QoI)

- Mode of Action: Cellular respiration

- Target Site: Complex III: cytochrome bc1

- Mobility: Locally systemic / translaminar, some are xylem-mobile

- Resistance Risk: High

The QoI fungicides, commonly known as strobilurins, are a relatively new group of fungicides, with the first fungicide in this group (azoxystrobin) released in 1996. Stobilurins are modeled after a naturally occurring fungicidal compound (strobilurin A) produced by Strobilurus tenacellus, a species of wood-rotting mushrooms. These mushrooms grow on pinecones and produce a fungicidal compound to suppress other fungi that compete for the same food source.

The target site of the QoI fungicides is the mitochondrial respiratory complex III, which is an integral membrane protein complex that couples electron transfer. The QoI fungicides bind to the quinone outside site of complex III and block electron transfer between cytochrome b and cytochrome c1 across the membrane. QoI fungicides are active against a broad range of plant pathogens. Most have locally systemic and translaminar mobility in plants, and some are also xylem mobile. These fungicides can have 7-21 days of residual activity.

QoI fungicides are considered high-risk for the development of resistance in pathogens. Currently there are more than 20 plant pathogens with some level of resistance to QoI fungicides, including Cercospora sojina (frogeye leaf spot) and Cercospora kikuchii (cercospora leaf blight) in soybeans (Zhang et al., 2012; Price et al., 2015).

Table 4. Group 11 QoI fungicide active ingredients (strobilurins) used in fungicides labelled for control of foliar diseases in corn.

| Common Name | Chemical Group |

|---|---|

| azoxystrobin | methoxy-acrylates |

| picoxystrobin | methoxy-acrylates |

| pyraclostrobin | methoxy-carbamates |

| trifloxystrobin | oximino-acetates |

| fluoxastrobin | dihydro-dioxazines |

Multiple Mode of Action Fungicides

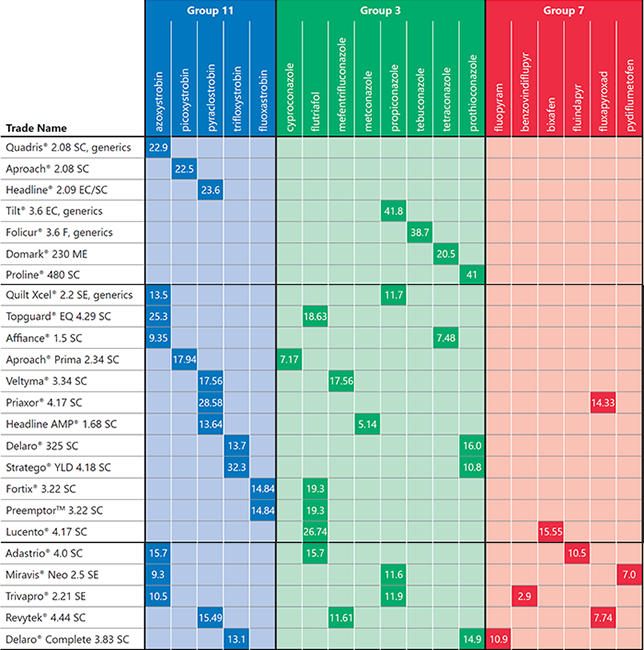

In the early 2000s, when foliar fungicides started to come into common usage in field corn, most fungicide products available to growers only included one active ingredient. Today, many fungicide products have multiple active ingredients. Numerous strobilurin + triazole products are available and strobilurin + triazole + SDHI products have become more common in recent years (Table 5).

Table 5. Active ingredients (%) by FRAC group of foliar fungicides labelled for use in corn (Wise, 2025). Click here or on the image below for a larger view.

One of the most important benefits of fungicide products with multiple modes of action is resistance management. Pathologists commonly recommend mixing or rotating fungicide modes of action to slow the development of resistance in pathogens. By using fungicides with different modes of action, growers can reduce the selection pressure on fungal populations, slowing down the development of resistance to specific fungicide types. This is important for preserving the effectiveness of fungicides, especially products such as the strobilurins, which are considered high risk for resistance development.

Fungicides with multiple modes of action can also provide more effective disease control by targeting a broader range of fungal diseases and pathogens and providing more comprehensive protection for the corn crop. Tar spot of corn (Phyllachorra maydis) has shown improved control when using multiple modes of action. Fungicide products with two or three modes of action provided greater suppression of tar spot than single mode of action fungicides in a multi-state study (Goodnight et al., 2024).

References

- Anderson, N.R., A.G. McCoy, C. Castellano, M.I. Chilvers, E. Alinger, T.W. Allen, K. Bissonnette, D. Copeland, N. Hustedde, T.A. Jackson-Ziems, N. Kleczewski, C. Leon, J. Mueller, P. Price III, R. Raid, A.E. Robertson, E.J. Sikora, D.E.P. Telenko, M. Wiggins, and K.A. Wise. 2024. Sensitivity of the causal agent of northern leaf blight of corn, Exserohilum turcicum, to the Demethylase-Inhibiting Fungicide Flutriafol. Plant Health Progress 25:287-292.

- Fungicide Resistance Action Committee. 2015. List Of Species Resistant to SDHIs April 2015.

- Fungicide Resistance Action Committee. 2024. FRAC Code List 2024.

- Goodnight, M., D.E.P. Telenko, T.J. Ross, M.I. Chilvers, T.W. Allen, K. Ames, A.M. Byrne, J.C. Check, W.S. Jay, B. Mueller, C. Rocco da Silva, E.M. Roggenkamp, S. Shim, D.L. Smith, A.U. Tenuta, and N.M. Thompson. 2024. Multi-state Fungicide Efficacy Trials to Manage Tar Spot and Improve Economic Returns in Corn in the United States and Canada. CPN-5015. Crop Protection Network. DOI: doi.org/10.31274/cpn-20240904-0

- Mueller, D., and A. Robertson. 2008. Preventative vs. Curative Fungicides. ICM News. July 29, 2008. Iowa State University.

- Mueller, D.S., K.A. Wise, N.S. Dufault, C.A. Bradley, and M.I Chilvers. 2013. Fungicides for Field Crops. APS Press. The American Phytopathological Society. St. Paul, Minnesota.

- Oliver, R.P., and J.L. Beckerman. 2022. Fungicides Mobility. In: Fungicides in Practice (pp. 119-126). CABI.

- Price, P.P., M.A. Purvis, G. Cai, G.B. Padgett, C.L. Robertson, R.W. Schneider, and S. Albu. 2015. Fungicide resistance in Cercospora kikuchii, a soybean pathogen. Plant Disease 99:11.

- Wise, K. 2025. Fungicide Efficacy for Control of Corn Foliar Diseases. Crop Protection Network CPN-2011-W.

- Zhang, G.R., M.A. Newman, and C.A. Bradley. 2012. First report of the soybean frogeye leaf spot fungus (Cercospora sojina) resistant to quinone outside inhibitor fungicides in North America. Plant Dis. 96:767.

The foregoing is provided for informational use only. Contact your Pioneer sales professional for information and suggestions specific to your operation. Product performance is variable and depends on many factors such as moisture and heat stress, soil type, management practices and environmental stress as well as disease and pest pressures. Individual results may vary. Pioneer® brand products are provided subject to the terms and conditions of purchase which are part of the labeling and purchase documents